This is a video of the Inaugural Address of GSG Impact Summit 2017 presented by CEO Amit Bhatia.

Recorded at the GSG Impact Summit in July 2017, this video show Sir Ronald Cohen’s closing remarks.

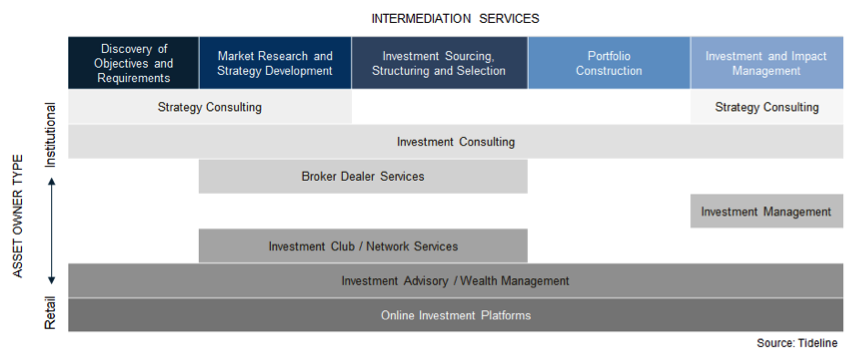

‘Intermediaries’ can help with deal discovery, portfolio construction — and impact measurement

By Fran Seegull, U.S. Impact Investing Alliance and Christina Leijonhufvud, Tideline It’s a good problem to have: traffic jams are starting to occur in impact investing. The growing demand and increasing capital for impact investment products and services means a growing network of consultants and advisors, broker-dealers, investment clubs, online platforms, and membership organizations. For example, nearly three dozen impact investing advisors answered the recent request for proposals from the Jesse Smith Noyes Foundation, according to Steven Godeke, the foundation’s vice-chair and an independent consultant. The increasingly crowded field of both well-established and newly formed “intermediaries” is a sign of a growing market that is increasingly able to meet the needs of a range of institutional and individual investors. These intermediaries are the connective tissue that binds asset owners and investment managers. But while extensive discussion in impact investing has taken place regarding the respective challenges of asset owners and managers, the intermediary landscape has received comparatively less attention. As a result, there is a need to bring greater clarity to the services that general and specialized impact intermediaries provide — from discovery through to portfolio construction and investment management — and to identify opportunities for reducing duplication, sharing best practices, and stimulating collaboration when appropriate. Without additional clarity, many asset owners remain confused about the type of intermediary best suited to the task, or even what their specific needs are as they move though the impact investment process.

To be sure, there are good reasons for redundancy among intermediaries as every service provider seeks to respond to the evolving needs of clients and prospects.

But there are signs the market is not connecting supply of and demand for capital as efficiently as possible, leading to suboptimal investment processes and outcomes that threaten the still-maturing market of impact investing.

To create a forum for candid discussion and exploration of potential solutions, the U.S. Impact Investing Alliance and Heron Foundation recently convened a private roundtable of approximately 30 intermediaries and asset owners.

Without additional clarity, many asset owners remain confused about the type of intermediary best suited to the task, or even what their specific needs are as they move though the impact investment process.

To be sure, there are good reasons for redundancy among intermediaries as every service provider seeks to respond to the evolving needs of clients and prospects.

But there are signs the market is not connecting supply of and demand for capital as efficiently as possible, leading to suboptimal investment processes and outcomes that threaten the still-maturing market of impact investing.

To create a forum for candid discussion and exploration of potential solutions, the U.S. Impact Investing Alliance and Heron Foundation recently convened a private roundtable of approximately 30 intermediaries and asset owners.

The highway

Think of the intermediary landscape as a “highway.” Intermediaries are vehicles for hire that carry passengers — the asset owners — along some part of their journey to deploy capital to impact investment opportunities that fit their values and preferences. In an ideal world, each lane on the highway would be clearly marked for use by a particular vehicle type. Explicit rules of the road would make it safe to switch lanes and overtake other vehicles, for example. Certain vehicle types might only transport passengers for a certain leg of their trip, with passengers transferring to another vehicle for the next leg. The intermediation vehicle or service required by an asset owner depends heavily on that asset owner’s objectives and where they are on their impact investment journey. For the early market research and strategy development legs, a strategy consultant might be best positioned. When the time comes for specific investment or portfolio construction recommendations, an investment advisor or wealth manager is better suited to take the driver’s seat. Similarly, an investor looking for a higher touch experience of deal sharing, due diligence and peer learning might benefit from an investment club or network as a complement to an investment advisor or wealth manager responsible for implementation across the investor’s broader portfolio.Road hazards

The current state of the intermediation highway highlights a number of key challenges and risks: 1. The opacity of functions and services across categories. Intermediaries are not always playing to their core strengths as they compete to acquire clients in a growing, but still limited, market. The results are often duplication of functions, market confusion, and substandard services for asset owners. Picture our highway without lane markings or road signs, traffic weaving together in fits and starts as drivers struggle to understand the rules of the road. 2. Lack of clarity by asset owners about their objectives and requirements. At the outset of an impact investment journey, it is important to recognize the need for strategy setting and discovery processes — tasks which are even more demanding when impact goals are layered onto investment decisions. Even when asset owners acknowledge the need for such services, the highly customized, inefficient nature of discovery can be difficult for even the most specialized intermediary to provide efficiently. Intermediary drivers on our highway are receiving unclear and inconsistent directions from their passengers, so that even when the lanes are clear, they may be compelled to make frequent and unexpected changes. 3. Both boutique and institutional intermediaries find it difficult to price their services to match the resources required to fulfill them. Pricing is especially difficult when such services are ancillary to their core business model. Hidden costs at a system level result. On the intermediation highway, large long-haul trucks are stuck in the passing lane and compacts are straining to tow heavy cargo.Traffic flow

A confusing, crowded, and uncoordinated intermediary landscape may be a necessary symptom of the market’s formative stage of development. The next stage, said participants at the roundtable held at the Ford Foundation, requires greater transparency, clearer segmentation and coordination, and increased collaboration among a diverse group of intermediaries. They recommended:- A regular forum for sharing insights and testing new ideas, which could also provide a venue for developing and defining best practices for service provision at each phase of the investment process; and

- A more unified language and taxonomy for articulating asset owner preferences and requirements, which would improve the matching process between asset owner and intermediary types.

Our history in impact investing: Program-related investments (PRIs)

This decision was a long time coming, and would not be possible if not for the hard work of so many pioneers and visionaries in the impact investing community. Indeed, it represents the next step in a long march that stretches back to the very beginnings of impact investing. Fifty years ago, in April 1967, Ford Foundation staff presented a report to trustees, titled Program-Directed Investments. It argued that philanthropy was about more than grant making. Our predecessors believed that philanthropy “should be viewed as a continuum of contractual options with the outright grant placed at one extreme, something close to a market investment at the other, and in between a series of alternatives representing ascending degrees of gifting.” The following year, the foundation sought and received a ruling from the IRS that allowed us to create a new investment vehicle called program-related investments, or PRIs. By law, PRIs are charitable investments. They take the form of loans, guarantees, and equity. These investments are directly aligned with a foundation’s programmatic commitments and must meet legal charitable standards, as well. Like grants, PRIs generally come out of a foundation’s program budget and count toward the 5 percent foundations are required to pay out every year. Unlike grants, PRIs are expected to be repaid. They are not, however, expected to provide a return at competitive, risk-adjusted market rates. PRIs often allow for both higher levels of risk and lower levels of financial return than conventional financial investments. We have found PRIs to be one of the most effective arrows in our quiver. Since 1968, the foundation has directed more than $670 million to PRIs, supporting social entrepreneurs and community development institutions around the world in their efforts to, among other things, preserve affordable housing, improve access to financial services and markets, create quality jobs, and advance arts and culture. And, as expected, our PRI fund has broken even—or better—over time, while making catalytic investments. PRIs allow us to take risks consistent with our mission in ways that much larger investors, such as banks and pension funds, often cannot or will not. Our predecessors of 50 years ago understood that philanthropy is a spectrum with a host of options—options that have continued to grow and mature over the decades. While PRIs have allowed foundations like ours to tap the power of our grant-making budgets in novel ways, today, our mission compels us to explore how we might mobilize our most significant financial resource: our endowments.The next step: Mission-related investments (MRIs)

At its most basic level, philanthropy always has been about directing financial capital to solve social problems. And foundations always have had a unique relationship to our capitalist system, a relationship I explored two years ago in my essay “Toward a New Gospel of Wealth.” I am often reminded of how Henry Ford II urged our forebears to “examine the question of our obligations to our economic systems.” He asked that we consider how philanthropy, “as one of the [market] system’s most prominent offspring, might act most wisely to strengthen and improve its progenitor.” This obligation has become more pronounced in recent years. As a global foundation committed to fighting injustice, it is not lost on my colleagues and me that the very same systems that produce inequality also created our endowment, which, wisely invested, continues to fund our fight against inequality. Since our mission has been funded by returns on our endowment, we have come to believe, firmly, that we have a special responsibility—and unique opportunity—to help influence the very markets that allow us to operate. Clearly, one way we can do this is by taking a measured and carefully considered step to experiment with new kinds of investments that enlarge the meaning of the word returns. This is not a new consideration. Concerns about socially responsible investing go back to the founding of modern stock markets centuries ago—and debates about reconciling the gains in “sin stocks” with ethical standards and religious values. Since the 1980s, divestment movements around the world have asked institutional investors, in particular, to consider how their investments are related to the wider world. Whether they were demanding divestment from tobacco, fossil fuels, or apartheid South Africa, these movements reminded us that our investments are part of a broad ecosystem of consequences, intended and unintended—consequences that we realized we could not ignore. Today, we have an opportunity to build on this proud, powerful legacy. Previous divestment movements tried to prevent investors from harming society; now, institutional investors can begin to move from “do no harm” to exploring how to “do more good.” That brings us to mission-related investments, or MRIs. Through this new tool, we will leverage the power of our endowment, and start to unlock the potential of the 95 percent to create impact through the market. MRIs seek to achieve attractive financial returns while also advancing the foundation’s mission. Unlike PRIs, MRIs can bring to bear large amounts of capital in the service of multiple bottom lines.Why now: The changing landscape

The Ford Foundation is not the first to commit a portion of its endowment to MRIs. We follow in the footsteps of—and are learning from—those foundations that pioneered the use of this tool. They include the early signatories to the More for Mission movement, as well as a number of other foundations that have announced new and significant initiatives in recent years, including the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Kellogg Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Kresge Foundation, McKnight Foundation, F.B. Heron Foundation, Wallace Global Fund, Surdna Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Open Society Foundations. While these institutions have taken a variety of approaches, their commitment demonstrates leadership and courage. Their initial steps should inspire all of us to consider how we might leverage the power of our endowments to promote dignity, equality, and justice for people around the world. Significant changes in the capital markets have also made this step much easier for us to explore, and hopefully for others to consider, too. All manner of financial institutions, from private wealth advisers to large asset owners, are now deploying investment products to meet the rapid increase in investor demands for sustainable investments. In the past, there have been three main reasons why most American foundations have not invested any portion of their endowments into MRIs. First, legal uncertainty served as a barrier. Until recently, it was not clear whether MRIs could meet the prudent investor standards that government sets for how foundations can invest their endowments. But last year, the United States Treasury clarified its position, establishing the legality of MRIs as part of a larger effort to encourage them. Second, there have been legitimate questions about whether there is enough evidence to prove that mission-related investments yield desirable financial or social returns. We’ve come to realize that if we hope to answer this second question, it is our responsibility to put more of our money where our mouths are. For this promising sector to continue to grow and mature, it needs more data, which requires a greater depth of experience and a greater measure of leadership. While the Ford Foundation has previously been willing to commit grant dollars, we are now excited to take the next step and commit endowment dollars, too. The experience of others has given us reason to be optimistic, as has the continued growth of the field. For example, over the past few years the tools available to measure social impact have become increasingly precise, thanks in large part to the work of several leading institutions:- The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), an independent council, has worked to standardize corporate reporting of material nonfinancial data in areas like employment, environmental sustainability, and governance.

- An initiative of the Global Impact Investing Network, IRIS(Impact Reporting and Investment Standards) is a catalog of accepted performance metrics that helps guide investors who want to consider their social and environmental impact.

- The Global Impact Investing Ratings System (GIIRS) rates companies and funds based on their environmental and social impact, in a manner similar to Standard & Poor’s credit risk ratings. GIIRS is hosted by B Lab.

- The Mission Investors Exchange is the leading network of foundations committed to collective learning and mobilizing their assets in ways that align with their mission.

Our decision

And so, for our part, the Ford Foundation has decided to gradually and prudently invest up to $1 billion of our endowment in MRI funds, to be phased in over the next 10 years. This decision is a natural extension of our history of PRI investing, which will continue to play an important role in our approach to impact. It is deeply rooted in our ongoing program work to build more inclusive economies, help mature the impact investing sector, and fulfill our special obligation to help move market-based economies toward “the high road”—squaring the dynamism of markets with society’s highest values, especially fairness and human dignity. This work represents a new frontier for us, and will require new people with new skills. So, we will build a special team of dedicated, veteran investment professionals to manage our MRIs. Unlike our excellent, existing investment team, this group of financial analysts and advisers focused on MRIs will report to our program leadership, and be held accountable for social and financial returns that contribute to our mission and, over time, to our annual programmatic payout, as well. As for the objective of our MRIs, our early efforts will target areas that have long been central to our mission of disrupting inequality in all its forms. In the United States, we’ll start by examining investments that make housing more affordable and inclusive. And in developing countries, we’ll look at how MRIs could expand access to vital financial services, particularly for low-income and other underserved communities. Not only will what we invest in reflect our values—how we make these investments and report on them will be informed by our mission, as well. We hope to make diversity, equity, and inclusion bywords of this investment movement, paying attention to the makeup of investment teams, as well as where they invest and with what values. We join a growing number of committed pension funds, universities, foundations, and other institutional investors in not only considering diversity and inclusion but also recognizing how it can be a powerful contributor to performance and impact. And we will make our financial and impact performance completely transparent, to help move the wider marketplace forward. In every way possible, we will work to ensure that these MRIs complement the work we are already doing through our grant making and PRIs, and contribute to our larger vision for a more equal, more just world. And to be clear: This careful, gradual allocation of some endowment resources to MRIs will have little to no impact on our grant-making budget. We believe we can achieve attractive financial returns while also contributing to meaningful social progress by following a steady, deliberative approach, building in strong oversight and risk management by our board of trustees, and working fully with partners in the private, public, and nonprofit sectors. Throughout this process, we will learn as we go and share as we learn.The next great challenge for philanthropy

Of course, while I am profoundly pleased that the Ford trustees have made a significant commitment to MRIs, we know that a billion dollars—despite being a lot of money—is not nearly enough to grow and prove this space. One of my former colleagues, Antony Bugg-Levine, a founder of the impact investing movement, has framed the problem presciently. He often says that our social challenges and social capital form a kind of ledger, with liabilities on one side and assets on another. The fact is, we face trillions of dollars in risks and liabilities—whether from environmental degradation, disease burden, lack of affordable housing, persistent joblessness, the impact of structural and systemic racism and gender bias, or so many other drivers and consequences of inequality—compared with only a few billion dollars of philanthropic assets. With the gap so wide and the stakes so high, we cannot afford to leave any option unexplored. My conviction is that this moment offers us an opportunity to help capital markets become accelerators of justice. And my hope is that, before long, many more foundations, of all kinds and sizes, will find ways to tap the power of their own endowments to help contribute to multiple bottom lines. Pension funds, university endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and others can do the same, in ways consistent with their respective missions, expertise, and fiduciary obligations. In time, I fervently believe, we will see a thriving, mature sector in which everyone can make impact investments that produce both sustainable financial returns and substantial social returns. Maybe it will take decades more to get there. But we’ll never know if we don’t make a start. Since the birth of foundations, our endowments have been essential to our work. Going forward, I believe they will become an essential part of our work and how we continue that work into the future. This is the next great challenge in philanthropy: to find and finance more social good than we ever have before. It is a challenge we will rise to meet together.

Imprese sociali, quella spinta che può arrivare dall’Unione bancaria europea

Sono passati già 9 anni dal fallimento della Lehman Brothers: l’inizio della terribile crisi finanziaria del 2008, un terremoto di cui paghiamo il prezzo ancora oggi. Pochi anni dopo l’Unione Europea ha reagito con l’unione bancaria a livello europeo, una regolamentazione uniforme nata per armonizzare le competenze in materia di vigilanza, risoluzione e finanziamento e per assicurare che le banche assumessero rischi calcolati e pagassero il prezzo di eventuali errori commessi. L’unione bancaria ha rappresentato un obiettivo ineludibile per completare l’unione economica e monetaria e per aggiungere un tassello importante alla costruzione europea. Il 2017 è l’anno della manutenzione di queste regole bancarie europee, e con Social Impact Agenda per l’Italia, l’Associazione nata per promuovere gli investimenti ad impatto sociale in Italia, vogliamo sfruttare questo momento per ottenere una regolamentazione capace di favorire una finanza generatrice di valore reale e sociale. La strada è stata aperta l’anno scorso da una coalizione di organizzazioni italiane (tra cui figuravano BCC Federcasse, ABI, Confindustria e altre associazioni imprenditoriali italiane) che ha proposto e ottenuto l’estensione del sistema che prevede accantonamenti di capitale più bassi per le banche che concedono prestiti a piccole e medie imprese. Sistema conosciuto come lo SME supporting factor che di fatto rende più semplici l’erogazione di prestiti a queste categorie di imprese, ritenute, a ragione, un volano dell’economia reale. Social Impact Agenda per l’Italia si muove sulla scia di questa esperienza per estenderla. L’idea è di estendere il regolamento CRR art.501, che introduce l’SME supporting factor, anche ai crediti erogati alle imprese sociali (Social Economy Enterprises) attraverso un nuovo SEE supporting factor. L’SEE supporting factor quindi consentirebbe di modificare quel trattamento prudenziale applicando a quelle imprese un coefficiente di assorbimento pari al 60%. Tale strumento ridurrebbe gli oneri di accantonamento di capitali da parte delle banche per i crediti erogati alle imprese del Terzo Settore e si configurerebbe come un mezzo prezioso per facilitare l’accesso al credito all’economia sociale. Insomma, un incentivo non da poco per le imprese del Terzo Settore che spesso devono ricorrere al prestito bancario per anticipare quote di denaro che vengono restituite agli enti finanziatori come rimborso di spese effettivamente sostenute. Tra l’altro la minore rischiosità del terzo settore, sperimentata nella pratica da diversi istituti bancari e in primis dalle BCC, incoraggia questo tipo di azione. Le imprese sociali rappresentano un tratto importante del futuro dell’economia italiana ed europea, contribuiscono a ricostruire un’economia generatrice di valore e capace di rispondere a vecchi e nuovi bisogni sociali. Con l’aggiornamento dei regolamenti dell’unione bancaria l’Unione Europea ha la possibilità di ripartire da ciò che conta, da ciò che è reale, dall’economia che produce valore. This article first appeared on sociale.corriere.it.

Achieving the SDGs requires greater investment than governments alone can provide. How can we ensure private investors see the value in supporting programmes that offer more than just financial returns?

Over the last 20 years, new actors and intervention models have radically changed international cooperation. First, we have seen the development of ‘South–South’ cooperation promoted by emerging countries, at the expense of models based on the expertise and culture of traditional donors. At the same time, the role of private foundations and their support of economic and social activities has increased dramatically. Finally, the private sector has started to adopt a ‘shared-value’ perspective towards investing resources and creating business initiatives in developing countries. All these factors are creating and encouraging hybrid models, which look at both financial sustainability and social impact – these models are gradually smoothing over the differences between the profit and non-profit sectors. In several official situations, the international community publicly defined and shared some principles and rules. These have legitimated and encouraged new actors and models within development aid, which is now not exclusively restricted to NGOs or the publicly funded. For instance, Millennium Development Goal 8 outlined the importance of creating a global partnership for development. It underlined the importance of the private sector as a supplier of the economic resources and technical know-how to enable international cooperation programmes to aim for social and economic sustainability. Recent international gatherings such as the Monterrey Conference (2002), Busan Conference (2011) and Doha Declaration (2008) have all moved in the same direction. The private sector, identified as the for-profit sector, has been presented as a relevant player for international cooperation – not just as a sponsor of economic resources, but also as a partner for building strategic relationships and innovative development models. This perspective is creating a variety of new tools and opportunities in the fight against poverty and other social global issues. We need to strategise and coordinate all these different models, instruments and objectives to maximise their effectiveness and impact across the globe. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) represent a shared framework that identifies the resources necessary to face the challenges of global issues such as access to clean water, healthcare and wellbeing and climate change mitigation. They encourage the creation of a global partnership where governments, civil society and the private sector can actively cooperate. The involvement of the for-profit sector implies that, on the one hand, governments would be well advised to implement policies favourable to private investments. On the other, it suggests that private companies should refocus their investments towards sustainable initiatives that take into account environmental, social and governance criteria and where the economic returns are spread over a longer timeframe. Impact investments In this scenario, ‘impact investments’ assume an important role in strengthening businesses’ initiatives that help to address global issues. As defined by the Social Impact Investment Taskforce, established under the UK’s presidency of the then G8 group of countries in 2013, impact investments are those made with the intention of generating positive social and/or environmental impact alongside a financial return. In recent years, impact investors around the world have demonstrated the potential for the private sector to drive progress in areas such as affordable housing, access to financial and health services, sustainable energy and other areas that clearly align with the SDGs. The UN’s World Investment Report 2014 estimated that to achieve the SDGs, we need to fill a funding gap of $2.5 trillion a year. According to the same report, the private sector has the potential to invest some $1.8 trillion of that. However, this will be difficult without adapting a range of financial tools that can facilitate private-sector investments in the SDGs. Over the last few years, the social impact finance sector has developed numerous innovative investment products to mobilise both private and public investors, as well as additional resources from other actors such as NGOs and development agencies. These include: Sustainable development bonds (SDBs): these are debt securities issued by private or public entities to finance activities or projects linked to sustainable development. SDB issuers state the interest rate that will be paid and the time at which the original investment amount must be returned. Development impact bonds (DIBs): these bring together private investors, non-profit and private-sector service delivery organisations, governments and donors to deliver results that society values. They provide upfront funding for development programmes from private investors. The investors are remunerated by donors or host-country governments – and make a profit – if evidence shows that programmes achieve pre-agreed outcomes. If interventions fail, investors lose part or all of their investment. Challenge funds: these are financial instruments promoted by organisations such as development agencies, private foundations and NGOs. They are linked to a specific objective or outcome. Debt and equity investments: these are investments that are suitable for sustaining social enterprises whose aim is to create a benefit for particular groups of people or to generate a positive impact for the environment. These various financial instruments should also improve the effectiveness of the resources invested by promoting innovative models of intervention. Impact investing can stimulate and encourage public policies in experimental programmes and, above all, attract private investments, promote technical solutions and build new capacities. DIBs can be an effective way to create greater accountability among parties cooperating on international interventions. The evaluation of the bond’s impact is central to this purpose, generating estimates for financial return and social impact based on the results of similar kinds of deals. Developing synergies Social impact measurement practices also require us to set measurable objectives and track their achievement. As stated in the Social Impact Investments Taskforce’s report, The Invisible Heart of Markets: “Specifically, effective social impact measurement is needed by five key market participants: government, foundations, social sector organisations, impact-driven businesses and impact investors. They all have a broad interest in a wide range of metrics (including the gain to society resulting from a successful intervention, and the associated social rate of return on investment).” Overall, impact investment instruments are encouraging synergies among several actors. Private investors are investing financial resources and are assuming part of the risk of the interventions. NGOs are offering their knowledge of contexts and their capacity for involving beneficiaries in the programmes. Governments and donors are cooperating on outcome-based models that define development priorities. Together these actors can work efficiently to realise sustainable solutions and give their significant contribution to the achievement of the SDGs. This article originally appeared on sustainablegoals.org.uk.